Building Tidepools – Interstitial Public Interest Infrastructure(s) for Unstable Times

Written by Sean McDonald

The social sector needs tidepools. A tidepool is an ephemeral ecosystem that captures just enough water to sustain life until a new tide comes in. Tidepools aren’t permanent solutions, they’re a place for those at risk in changing tides to pause, regroup, and prepare for the water to rise again.

In 2025, the tide of government and government-adjacent support for the social sector went out fast – and a wide range of these are being forced to react. And those reactions vary a lot – both in what they’re trying to achieve and how they’re implemented. At a high-level, there are a few noticeable trends:

- The collapse of a wide range of funding supply chains and operating environments has created a cultural moment in civil society, where leaders are, by necessity, prioritizing building capacity for mission-aligned evolution;

- There has been an incredible amount of ad hoc and organized effort put into archiving and replicating precarious data sets and technologies, but comparatively little into preserving means of production;

- Many social sector organizations are having to make difficult decisions, between spending limited time and resources on whether to prioritize active stewards or stable archives for their work, which is financially, politically, and practically complex;

- There is an ongoing shift, from prioritizing a focus on upstream funders – whether government, philanthropy, or investor capital – to focusing on value to users and use-based revenue models – with impacts on business models, scale of operation, and significant, often political, impacts on whose interests are prioritized;

- The typical timeline for a merger, acquisition, or some form of strategic integration is approximately two years, which may or may not be compressible by necessity;

- Even where successful in navigating to new stability, most organizations are unbundling in-part or in-whole, leaving whole lines of un-funded programs and practice areas behind – often without a clear succession plan for their work, learnings, and products.

Through the work of supporting public interest and civil society organizations through rapid ecosystem change, we’ve seen an incredible need for, and value in, tidepool infrastructures. Social sector work and projects

Tidepool infrastructures are operational spaces whose primary function is to help sustain an ecosystem or a critical component of an ecosystem between surges. Tidepool infrastructures, unlike actual tidepools, are intentionally designed to bridge practical capacity gaps without necessarily being (or intending to be) the permanent homes for the initiatives they serve.

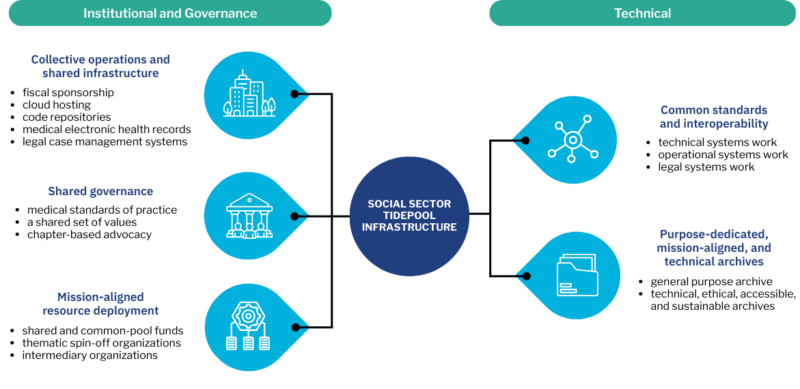

In a practical sense, tidepool infrastructures are organizational infrastructures that are capable of supporting, sustaining, and/or stewarding critical public interest work. And the good news is that the social sector already has a number of tidepool infrastructures, focused on ensuring that aligned actors can engage a wide range of collaborative functions, like:

- Collective operations and shared infrastructure – the variability and dynamism in scale of public interest organizations and technologies make sharing infrastructure a strategic necessity for many public interest projects. Whether that’s through organizational means like fiscal sponsorship (like the Tides Foundation, the National Philanthropic Trust, or Superbloom) shared technical infrastructures like cloud hosting (like Amazon Web Services, Cloudflare, or Azure) and code repositories, (like Github, Bitbucket, and Gitlab), or shared specialist services like medical electronic health records (like Epic) and legal case management systems (like Clio). Each of these tidepool architectures are designed to help projects grow mature and contract as their work and needs require.

- Data production initiatives – there are a range of social sector initiatives designed to create public interest and independent data sets, whether of Internet connectivity, environmental conditions, or human rights documentation. These organizations are tidepools in the sense that they exist to provide a source of information lots of third-parties rely on, but are not integrated into their organizational or business models.

- Shared governance – organizations and individuals often team up in order to represent a core, shared interest, like medical standards of practice, or a shared set of values, like chapter-based advocacy. Here, tidepools steward a specific element and harness the legitimacy of the organizations and people they represent.

- Mission-aligned resource deployment – in the social sector, pooled investment and grant funds are often administered through tidepool infrastructures – like shared and common-pool funds, thematic spin-off organizations, and intermediary organizations;

- Common standards and interoperability – a lot of technical, operational, and legal systems work on establishing common standards, whether for interoperability, security, or the implementation of a compliance regime. These tidepool infrastructures govern the shared externalities and attempt to identify, resolve, and share solutions to problems faced by public interest (and especially digital) spaces;

- Purpose-dedicated, mission-aligned, and technical archives – there’s a lot of work that goes into sensemaking – especially during moments of organizational transition. The first step is often to try and find a general purpose archive, like a university, library, or the Internet Archive, to host (at least) a copy of the work being preserved, but the purpose of that preservation is, of course, future use. In the public sector, organizations not only want to preserve availability, they want to preserve work in-line with their mission and, hopefully, in ways that preserve their underlying value (for future use). Each of these archives are tidepool infrastructures – and there is substantial work involved in ensuring technical, ethical, accessible, and sustainable alignment in preservation spaces.

Ultimately, tidepool infrastructures tend to be places where a range of actors unite in a shared pursuit, whether it’s learning from cutting edge research, setting shared standards, collaborative sensemaking, independent governance, collective bargaining for specialist services, alignment in resource deployment, or practical preservation. While that’s what tidepool infrastructures “do,” their very establishment and ongoing existence both represents and teaches significantly more. For example they provide practical and cost-savings for operations. They function as collective and civic engagement mechanisms to support shared values. They metabolize learning into service designs and architectures. They recognize the need for resilience in uncertain environments. And they realize the value of lived experience and provide pathways for investments into future systems and solutions.

And while all of these infrastructures are valuable models, the existence of tidepools doesn’t ensure that everyone who needs them finds them. There are significant financial, personal, cultural, organizational, political, educational, practical, and governance challenges involved in navigating organizational changes across scale and context.

If anything, the huge dynamism in the public interest sector doesn’t appear to be going anywhere and so there remains a massive need for investment, innovation, and practical engagement with tidepool infrastructures.

We think the framing is helpful and would love to help identify, share, and support existing and emergent tidepool infrastructure organizations as they navigate the moment. If that’s you, or something you’d like to help with, too, reach out – hello@civicstrengthpartners.org